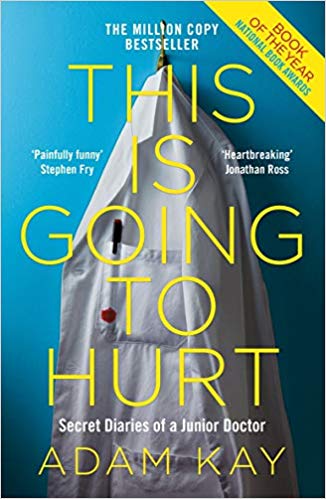

Adam Kay (2018), Picador, London.

280 pages, £4.99. ISBN: 978-1-5098-5863-7.

This

is Going to Hurt – Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor

Adam Kay (2018),

Picador, London.

280 pages, £4.99. ISBN:

978-1-5098-5863-7.

The author

Adam Kay was born in Brighton into a family of doctors and

educated at Dulwich College, Imperial College School of

Medicine and Imperial College, London. He

self-identifies as a Jewish homosexual, who lives with his

partner, James Farrell, known throughout the book as H.

And Kay is an abortionist – ‘I performed a large number of

TOPs [termination of pregnancies] in this job’ (p. 198).

And no, I am neither anti-Semitic nor homophobic, but I am

pro-life. Even so, I think I would enjoy dinner with the

author one evening, especially as he can now afford to

pay. Perhaps we should make it a light lunch because Kay

has a BMI of 24 (p. 211).

The book

We have a fascination and a fixation with the world of

medicine and hospitals and doctors. For example, think

TV shows like Dr Kildare and M*A*S*H through

to Casualty and Holby City. Books about

doctors, by doctors, are also much in vogue. Think Atul

Gawande, Henry Marsh, Oliver Sacks and Kathryn Mannix.

But This is Going to Hurt is rather different.

It is serious medicine with serious humour, droll doctoring,

but with an intense undertone and a sad, sad ending.

What also makes it different is its phenomenal success.

Published in 2017, This is Going to Hurt was Kay’s

first book and it has remained in the Sunday Times bestseller

list for almost 100 weeks with sales of well over one

million. His second book, Twas the Nightshift before

Christmas, appeared in October 2019.

The book consists of a collection of diary notes, apparently

secretly written while Kay progressed from lowly medical

student and house officer through the NHS promotional system

of senior house officer, registrar to senior registrar.

He chose to specialise in obstetrics and gynaecology – 'I

liked that in obstetrics you end up with twice the number of

patients you started with’ (p. 32). Yet, in 2010, after

six years of medical school and another six on the wards of

various hospitals, Kay resigned.

This is Going to Hurt is a book of two parts, or with

two interwoven themes. First, there is the very witty

account of life on the NHS frontline. Second, there is

the very heartfelt account of the struggles – medical,

bureaucratic and personal – of a junior doctor.

First, the witticisms appear on every page. Some are so

bizarre they seem fabricated, if not just a little overegged,

for publication purposes. For instance, there are

accounts of various peculiar objects that get stuck in various

bodily orifices, as well as the astonishing ignorance and

naivety of some expectant mothers and fathers. Then,

since Kay specialised in obstetrics and gynaecology, there are

alarming accounts of life and death situations, especially

those involving Caesarean sections, which mostly involve

jolly, if not always jovial, outcomes. Perhaps to try

and de-stress under his enormous pressure of work, much of his

humour is school boyish and genitally themed. On the

other hand, there are numerous educational footnotes giving

opportunity to brush up on obs and gynae terminology, such as,

colposcopy, cord gases, puerperal psychosis, primiparous and

ascites. And readers will have to endure repeated

gratuitous swearing – sadly, it has become the lingua franca

of our entertainment world and beyond.

Second, Kay’s personal struggles appear on almost every

page. Twelve-hour shifts, endless overtime, lack of

sleep, disrupted personal life, privation of food, inordinate

stress and strain, mindless bureaucracy, grumpy colleagues and

much, much more. As clients/users/patients of the NHS we

are typically delighted with its staff and their

performance. We routinely go into hospital sick and come

out better. The NHS is our national treasure. But

there is this other side. That free treatment for us

comes at a price to them. Here is Kay’s perspective (p.

198), ‘The hours are terrible, the pay is terrible, the

conditions are terrible, you’re unappreciated, unsupported,

disrespected and frequently physically endangered. But

there’s is no better job in the world.’

In conclusion

Suddenly, on p. 254, the diary format ends with an entry for

Sunday, 5 December 2010. There has been a crisis and Kay

is in the thick of it. He is the senior doctor on the

labour ward. A patient needs a Caesarean section for

foetal distress. His senior house officer wields the

scalpel and disastrously hits the uterus. Rather than

amniotic fluid, blood pours out, twelve litres of it in

total. There has been an abruption – the placenta has

separated from the uterus because of a previously undiagnosed

placenta praevia. Kay takes over, delivers the placenta

and the baby. The baby is dead. Kay and colleagues

fight to preserve the life of the mother. They do,

just. Kay cries for an hour.

This is the turning point of the book – there are no more

laughs. It is also Kay’s personal crossroads.

Though not negligent, he has failed himself. He is now a

different doctor. Bad stuff, sad stuff inevitably

happens in human medicine, but this was the deal

breaker. Kay could not continue with what he came to

regard as an absolutely impossible task. He took less

demanding jobs, ‘but after a few months I hung up my

stethoscope. I was done’ (p. 260).

Six years later, this book appeared. It closes with a

plea for the UK population to lobby the media and their MPs to

save and improve and fund our dear old NHS. Kay now

writes and script-edits comedy for TV.

Yet Kay’s call to arms may well fall on deaf ears. In

the week I finished reading this book, The Times of 25

February carried a piece by Carrie MacEwen, chairwoman of the

Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, which brings together 23

medical royal colleges and faculties. She stated that

doctors need to stop moaning and take responsibility for

improving the NHS. She said ministers have given the NHS

a ‘substantial sum’ of money and doctors must now stop blaming

the government for all its problems. Britain’s 220,000

doctors have a professional duty to make the health service’s

ten-year plan work and can no longer ‘sit on their hands’,

Professor MacEwen continued. After years in which the

loudest medical voices have tended to complain about

government funding and staffing levels, she said that doctors

should take advantage of a ‘golden opportunity’.

Kay and MacEwen are at loggerheads. They cannot surely

both be right. MacEwen is a consultant

ophthalmologist. One wonders, has she read Kay’s book

and when did she last work as a hospital senior registrar on a

hectically busy ward? And when does her current job

‘hurt’? We know when Kay’s did. And it ‘hurt’ him

so much it became too much. This is Going to Hurt

delivers an amusing read, but also a hefty emotional jolt.