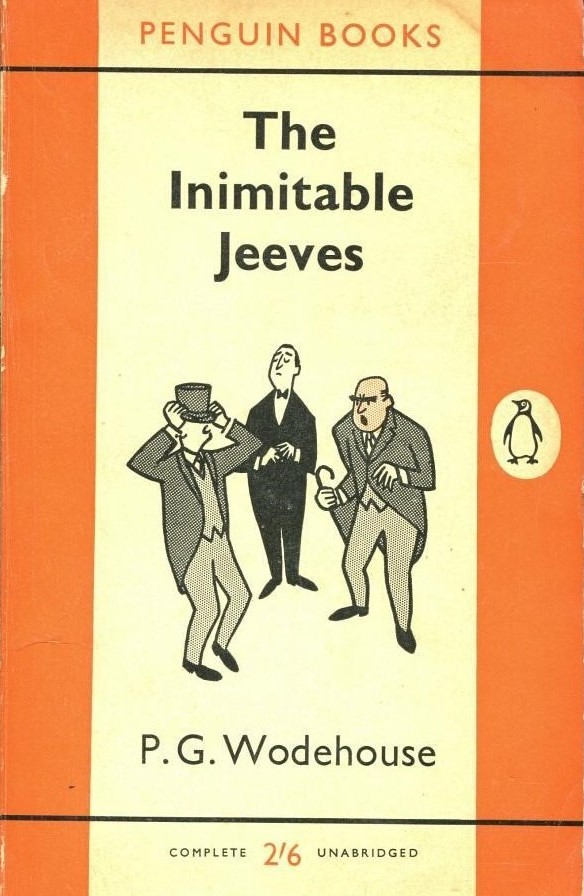

The Inimitable Jeeves

P G Wodehouse (1961), Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth.

224 pages, Two shillings and sixpence.

I say, sometimes when a chap has had his head stuck in sciencey stuff for an age, he jolly well deserves a sunny read. Know what I mean? So I dug out this little gem by P G Wodehouse. It had been sitting patiently on my shelves for decades. It's a Penguin classic, in those conspicuous old-style buff and orange colours, reprinted in 1961, and a decent snip at half-a-crown. I must have first read it as a young whipper-snapper, at university, or some such. Whatever, it has been a cheery antidote to all that rummy bioethical paraphernalia and what not. Absolutely top hole!

The author

Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was born on 15 October 1881 in Guildford, England. He quickly became known as ‘Plum’ to his family and friends. After being happily educated, along with his two older brothers, at various prep-schools and Dulwich College, he started out in banking – the year was 1900 and the City soon proved to be not for him. Meanwhile, he had been busily writing in his spare time, and two years later he secured a permanent position producing a regular column for The Globe newspaper.

He first visited America, his perceived ‘land of romance’, in 1904 and later sold two short stories there. He stayed put, writing for the Saturday Evening Post, which first serialised and published nearly all of his books. In addition, he turned his hand as a lyricist working with Jerome Kern, and as a scriptwriter of several Broadway shows, Hollywood films and straight plays. He was becoming a celebrated and a rich man.

In September 1914, he married Ethel May Wayman, an English widow. The marriage proved to be both contented and lifelong. Ethel and Plum were unalike – he was shy and impractical, whereas she was gregarious and decisive. Ethel ensured he had the peace and quiet he needed to write. There were no children from the marriage, but Wodehouse was devoted to Ethel's daughter from her first marriage, Leonora, and legally adopted her.

In 1916, the first of the Jeeves, that ‘supreme gentleman’s gentleman’, stories appeared. They turned a literary corner for Wodehouse. His readership grew from prep-school boys to admiring adults and approving critics. Hilaire Belloc regarded Wodehouse as the best living writer of English. J B Priestley called him superb. Sean O’Casey named him ‘English literature’s performing flea.’

In 1934, the Wodehouses moved to France for tax purposes. During 1940, he was imprisoned for almost a year by the invading German army. After his release he made six comic programmes, intended primarily for a US audience, but broadcast using a German radio station. It was an ill-conceived venture, which stirred up considerable rancour and political anger across Britain. Wodehouse never returned to the land of his birth.

In 1955, Wodehouse, the émigré, became an American citizen, but he remained a British subject so he was still eligible to be recognised for a UK honour. Three times he was nominated, but twice blocked by British officials. It was not until 1974 that the British prime minister, Harold Wilson, intervened and Sir Pelham was named in the January 1975 New Year Honours list. Many reckoned that the belated award marked the official forgiveness for his wartime indiscretion.

The honour was short lived. The following month, Wodehouse was admitted to Southampton Hospital, Long Island, for treatment of a skin complaint. While there, he suffered a heart attack and died on St Valentine’s Day 1975 at the age of 93. Four days later, he was buried at Remsenburg Presbyterian Church, New York.

The book

Some readers may recall the Wooster and Jeeves radio dramas of the 1970s starring Richard Briers and Michael Hordern as the title characters respectively. More readers will remember the early 1990’s ITV series of 23 episodes featuring Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry in the eponymous roles. The books are much older, dating from the 1920s. The Inimitable Jeeves first appeared in print in 1923 as the second collection of Jeeves stories and it has been reprinted many times since.

It is a tale in eighteen chapters. The plot is simple. First, the hapless Bertie Wooster is endlessly entangled by the antics of his friends and particularly his best chum, the continually love-sick and impecunious Bingo Little. Second, Bertie is constantly unentangled by his valet, the inimitable Jeeves, always on hand, always right. Other bit parts are played, for instance, by the domineering Aunt Agatha, the annoying twins Claude and Eustace, the patron Lord Bittlesham, and a galaxy of eligible gals. It is all quite preposterous … and yet.

The style

The book is set in 1920’s and ’30’s Britain – the late Edwardian era. And it bubbles with the appropriate upper-crust language. It is evocative of the schooldays of Tom Brown, Billy Bunter, and just about my own. It is the world of public schools, London clubs, the well-to-do and valets.

Wodehouse had a thesaural penchant for the age. Take, for example, the words he uses for a ‘man’. I’ve noted them as I have read the book. Here are some. Blighter, chap, poor prune, cove, excrescence, chappie, lad, chump, merchant, old bean, old thing, old sort, old egg, old bird, old gargoyle, old turnip, old scream, dear sweet thing, poor fish and unfortunate mutt. Magic!

From Wodehouse’s words to his turns of phrase. He leads the way with examples such as, ‘Hallo, hallo, hallo’, ‘don’t you know’, ‘all that sort of rot’, ‘and what not’, ‘rummy this and rummy that’, ‘toodle-oo’ and ‘what-oh!’ How gently they carry the reader back in time.

Then it is onto his masterful, yet restrained, comical sentences. Consider, the lovelorn Bingo pestering Bertie (p. 141), ‘… the Cynthia affair had jarred the unfortunate mutt to such an extent that he was always waylaying one and decanting his anguished soul.’ Or when Aunt Agatha almost met Claude and Eustace (p. 191), ‘Twenty minutes earlier and she would have found the twins gaily shoving themselves outside a couple of rashers and an egg.’ And Bertie relaxing (p. 199), ‘I was lying back on the old settee, gazing peacefully up at the flies on the ceiling and feeling what a wonderful world this was, when Jeeves came in with a letter.’ It may not be side-splitting stuff, but it is soft and droll, which is far more classy and gratifying. And oh, yes, there was no swearing or sex or smut, but there was also nothing specifically Christian either.

Each Wodehouse book underwent an intricate and protracted gestation. He would first write a few hundred pages of notes. Once the plot had been outlined, he would fill in the characters and their parts in a 30,000-word or so draft. All this might take up to two years, so Wodehouse would often be preparing two or more novels simultaneously. He worked at them seven days a week, preferably between 4 and 7pm, but never after dinner. As a young man, he would write between 2,000 and 3,000 words a day, although when in his 90s he was down to about 1,000 a day. Yet the final, polished prose was always fine in quality and ample in quantity. It reads with deceptive ease – the mark of the master wordsmith.

In conclusion

I was sorry to finish the book. I have not enjoyed such a piece of light fiction for ages. I looked on my book shelves and Amazon for another Wooster yarn, but eventually decided against it – never return to your honeymoon haunt, at least, not for a decade or two. That notwithstanding, I just might leg it down to Wooster-world sometime sooner. It provides a powerful antidote to the pain of non-fictional bioethical issues. As Bertie might say, ‘It would make a ripping jaunt’. Pip, pip.